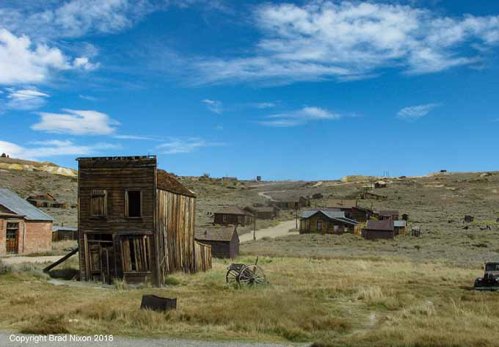

My recent trip north from Los Angeles along U.S. Route 395 included seeing the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest, Laws Railroad Museum and Bodie ghost town.

The semi-arid area between the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the west and Inyo and White Mountains to the east has innumerable other attractions which would require most of a lifetime to explore, including the highest peak in the contiguous United States — Mount Whitney — and Death Valley National Park, to name only two.

On the first day of the trip, I stopped for a repeat visit to Manzanar National Historic Site. There is, at first glance, little that’s remarkable about Manzanar except the view. It occupies 814 acres at the feet of the Sierra Nevada, overgrown with sagebrush and high desert chaparral. The views of the Sierras to the west and, to the east, the Inyo Mountains, below, are dramatic.

There’s only one structure of any size: a former high school auditorium.

What merits designating those mostly empty acres a National Historic Site? There are a few clues. Visible from U.S. Route 395 is a guard tower.

When you drive into the site, you’ll pass these sentry stations.

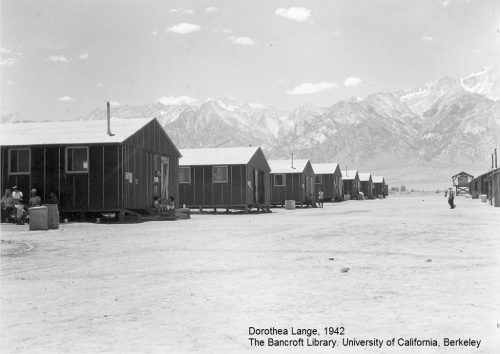

Driving further, you’ll find tarpaper-covered barracks.

The tower and barracks are reconstructions, representative of numerous other structures that once covered much of the site. It was a prison: Manzanar War Relocation Center. To name it more accurately, it was a concentration camp that held approximately 10,000 Americans of Japanese origin during World War II.

There were ten such centers, all built to hold people of Japanese origin or descent. The rationale was that all people of Japanese heritage — even if they were American citizens — represented a potential source of espionage and enemy sympathy. All the camps were in remote locations, invariably with difficult living conditions. There was summer heat and winter cold of deserts in California, Arizona, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming and Colorado; and swampy, mosquito-ridden lowlands in southeastern Arkansas.

More than 110,000 people spent the war years in the ten camps, taken into custody from the “Wartime Exclusion Zone” of California, Oregon, Washington, Hawaii and Alaska. They’d had only a matter of days to arrange what to do with the homes, businesses and belongings they left behind.

Manzanar’s internees came primarily from the Los Angeles area, and they lived at the camp from 1942 to 1945. At Manzanar, many worked at agriculture, crafts and a few professions, including medicine — work for which skilled doctors and nurses were paid a fraction of any existing professional rate.

More than 500 barracks, a hospital, post office and workshops are gone, as they are from all ten former camps. Today, driving around the site, the once-teeming city is evident only as scores of overgrown foundations, remnants of barracks, fields, gardens and playing fields. The Sierras loom in the west.

The internees formed social clubs, sports teams, churches and temples, and held classes on a variety of subjects. The Park Service has signposted most of the building and facility locations. Notably, residents published a newspaper, the Manzanar Free Press, established by an internee who’d been an editor for the long-running (still published) Los Angeles newspaper, Rafu Shimpo. A sign marks the site of the Free Press offices.

Visit Manzanar in summer, when the temperature can reach 110 degrees for days at a time, or in winter, when the wind blows down the valley with temperatures well below freezing, and imagine living every day in one of those tarpaper-covered barracks. Although the Sierra Nevadas rising to 14,000 feet are inspiring, I find it impossible to see them from Manzanar without a sense of irony.

The most evocative place in the park is the small cemetery, marked by a monument designed in 1943 by one of the internees, a stonemason, Ryozo Kado.

More than 135 Manzanar internees died during their incarceration. An unknown number were interred there, possibly as many as 80. All but a handful of the remains have been relocated in the passing years.

The three characters visible above — I REI TO — translated literally, say, “Soul Consoling Tower.”

In November 1945, three months after the war ended, the last inmates were released and Manzanar closed. Many were not returning “home,” because home was gone.

These are a few oversimplified facts about Manzanar, offered with a minimum of commentary about context, rationale for what happened or what Manzanar represents to me. If you’re unfamiliar with what happened 75 years ago, I encourage you to inquire further about it and the War Relocation Authority. This seems like an excellent time to discover if we can learn anything from history.

Visiting Manzanar

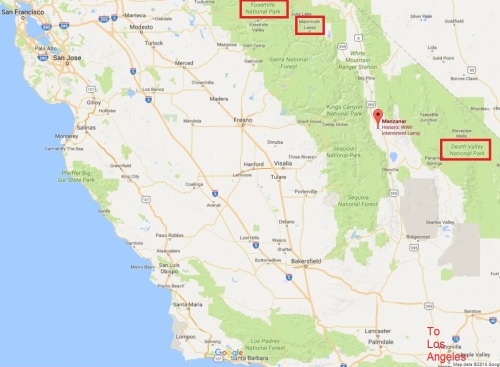

Manzanar National Historic Site is located on U.S. Route 395, which is also the road to reach Death Valley, Mammoth Lakes/Devil’s Postpile and the Tioga Pass entry to upper Yosemite Valley (red squares). About 3-1/2 to 4 hours from Los Angeles (below bottom of map), 7 hours from San Francisco (on left of map).

The site is open daily from dawn to dusk. There are no fees. The former Manzanar auditorium is the Visitor Center, where parking is free. The center includes extensive exhibits and artifacts of life at Manzanar. The park provides a driving tour guide brochure, the best way to survey the extensive site. The cemetery contains remains, and while photography is permitted, it merits appropriate decorum. Be careful turning off or onto busy Route 395. Vehicles are approaching at high speed across level ground, and will be upon you quickly.

Have you been to Manzanar? Or Jerome, Rohwer, Gila River, Poston, Tule Lake, Granada, Minidoka, Topaz or Heart Mountain, the other camps? Please leave a comment about what you saw there.

© Brad Nixon 2018. Some photographs © M. Vincent 2018, used by kind permission. Barracks photograph by Dorothea Lange, 1942; The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley. Map © Google with my emendations. Acknowledgment for information from Wikipedia, the U.S. National Park Service, the Manzanar History Association and the Densho Encyclopedia.

I’ve never been even to Tule Lake, which wasn’t that far from Ashland. Thanks, Brad.

LikeLike

By: Brian Doerter on October 13, 2018

at 4:43 am

So far as I can determine, there’s far less to see there than at Manzanar — and I think that’s true of all the other sites, too. The only way to visit it is via a ranger-led tour, only offered between Memorial Day and Labor Day. So, other than the opportunity to go from Ashland via Klamath Falls en route, and visit the Falls, it might not be visually stunning. One assumes there’s the same opportunity for reflection at all the sites, no matter the setting. Several are quite remote. And I know the joke about the falls, thank you.

LikeLike

By: Brad Nixon on October 13, 2018

at 9:56 am

What the internees at Manzanar made from the environment and situation summarily thrust upon them is a moving testament to the human spirit. It’s not as well-known, but residents of Italian origin were also subject to various restrictions and relocation to the camps. As you suggest, a time to reflect on this chapter in our history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: myeclecticcafe on October 13, 2018

at 12:26 pm

I can’t find it now, but I read a touching story about friends of an interred Japanese family who kept the family’s home and business intact while they were in the camps. Once the family was free to return home, they had a home to return to, and re-engaged in the business. Needless to say, that was not the norm.

I thought it was interesting that you used both ‘internee’ and ‘inmate’ in your post. I wonder what they’re calling the children at the camp in Tornillo, Texas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: shoreacres on October 13, 2018

at 5:58 pm

Not the norm, but there are many stories of people outside who performed similar favors, and many other Americans who were supportive, even participating in finding those in the camps places to live as part of a release program. One advantage we have is the fact that the WRA activities and events are relatively well documented, including some positives.

The use of words like “inmate” and “concentration camp” were once highly inflammatory matters. A long string of euphemisms have been used, but the thing speaks for itself, in much blunter language.

LikeLike

By: Brad Nixon on October 13, 2018

at 7:06 pm

Native Americans, the original and only true owners of the land that is now known as the United States of America, before this land was stolen from them by Europeans, have also been interned – permanently – in what are euphemistically called “reservations.” Has anyone asked these people how they like it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: LaBoheme on October 13, 2018

at 6:53 pm

Not in any real sense. A national shame, which continues.

This gives me an opportunity to cite an anecdote I left out of the post. Forgive me if I repeat anything I’ve said in another channel.

The two camps in Arizona were placed on Reservation land of two separate native nations. BOTH nations strongly objected to the government at having their land — to which they’d been “relegated” — used as a prison for OTHER American citizens.

LikeLike

By: Brad Nixon on October 13, 2018

at 7:08 pm