I’ve been doing some traveling recently, and I’m full of tales to be told. Despite what you might conclude from my posts of a week or so ago, I have not spent all my time on the road in luxurious hotels, although a couple of those were so remarkable, I couldn’t help but write about them. Now, just back from a trip to San Francisco and the Sonoma and Napa valleys, what better tale to relate than a visit to the former home of one of America’s greatest storytellers?

We don’t think about Jack London very much here in the 21st Century, but a hundred years ago, he was the most popular writer in America, at least, and, by some accounts, in the English language, period. It’s as an author that we think of him, of course, and even if you’ve never read a single one of his stories or novels, you probably have “Call of the Wild” or “White Fang” on the tip of your tongue, merely on his reputation alone. London was immensely successful as an author, earning a fortune solely on his publications, but his brief life encompassed far more than writing. Growing up in the San Francisco and Oakland area in dire poverty and struggle, he emerged to become a sailor, an adventurer, gold prospector in the Klondike, journalist, socialist firebrand, to name just a few of the threads of his life. As a self-made and largely self-educated man, though, he is full of contradictions and uncomfortable truths: so complex that not all of what is “true” about his life is easy to determine. He was not a writer who followed any academic or traditional course of education, maturation and fully-considered point of view. His writings and his actions were driven by the hardscrabble circumstances of his life and an unquenchable drive to succeed and to impose himself onto any enterprise that caught his interest.

I am not as well-versed as I’d like to be about either London’s life or his writing, so I won’t carry on about it. You’ll know as much as I know about his life if you read a brief biography, although I am glad to say I have read some of the stories and novels. Today’s account is of our visit to Beauty Farm, the thousand acres of land he bought in Sonoma County, near the village of Glen Ellen, just north of Sonoma. London embraced the planning and operation of his estate with typical fervor, and he makes an interesting comparison to Thomas Jefferson and other ambitious landholders of American history. Although you can hike over a lot of the ground in what London called The Valley of the Moon, now Jack London State Historical Park, and see surviving farm buildings and improvements, the most dramatic part of a visit to the Park is Wolf House.

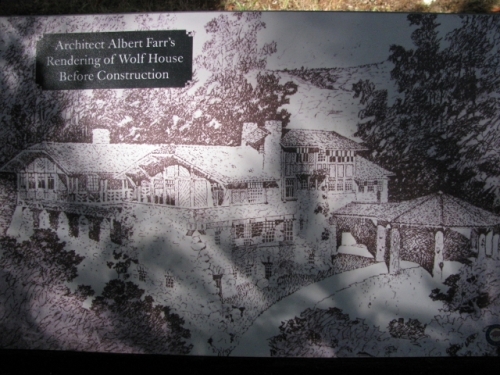

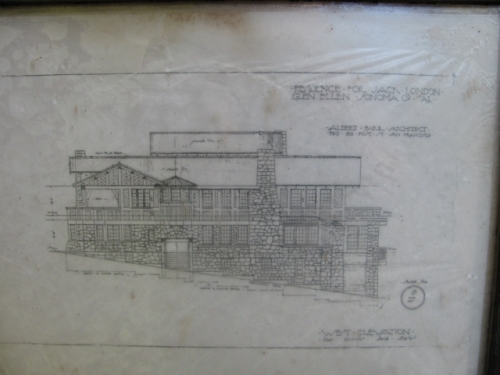

London envisioned a vast stone and timber lodge as his home on the estate. The drawings show a fascinating combination of the arts-and-crafts theme of that era (circa 1905) plus plenty of theatrical touches from London’s vast ego.

I photographed these drawings by London’s architect on our visit to the site. As you can see, it was an immense structure, with huge rock walls and massive timbers, on four levels. If you are not familiar with this story, and you wonder why I keep referring to the “site,” it is because the 15,000 square foot Wolf House WAS built. Then, in 1913, mere weeks before London and his wife were to move in, a fire destroyed the place.

London considered that Wolf House would stand for a thousand years.

Even its ruin may last that long, though it already requires shoring to support some of the walls that lack their timber roof frames for structural support.

Beauty Farm, itself, is not considered to have been a success. London, of course, was not a farmer, and probably should have had someone else operate the place. He was often absent, and, true to his nature, had some extreme ideas about how a farm SHOULD operate. But although he swore that he would rebuild Wolf House, he never managed it. He died in November, 1916, forty years old.

His ashes rest beneath a stone on a knoll just a few hundred yards’ walk from Wolf House.

Were it not for the madrones and redwoods that surround the spot, it would command a sweeping view of the Valley of the Moon, and one wonders if perhaps 90 years ago, some of those trees were not yet there. His wife, Charmian, survived until 1955, and her ashes are there too. I’m not big on Graves of the Famous Dead, and I’ve passed by many opportunities to visit other historic graves. Jack’s spot is a good one, though, and pays tribute to at least part of the man. It’s not easy to see how the beleaguered State of California will be able to preserve much of Beauty Farm over the long run. It’s not visited by hordes of tourists, given London’s fading memory in the popular culture, and most of the local attention goes to the wineries and restaurants that pack the Sonoma and Napa valleys.

We have his books, though. If you want to start with something short and powerful, read “To Build a Fire.” You won’t quickly forget Jack after that.

Visiting Wolf House

Wolf House is within Jack London State Historic Park near Glen Ellen, California, 1-1/2 hours’ drive north of San Francisco (it’s lovely country). In addition to the ruins, the cottage in which London and his wife lived in their later years is preserved, there’s a museum, and 20 miles of hiking trails.

© Brad Nixon 2010, 2017

Silenced you say? Who are you and what have you done with my brother?

LikeLike

By: Mark Nixon on October 27, 2010

at 7:06 am

All that, and he knew how to kill bedbugs as well – spent a short and much despised time as a laborer in a steam laundry. Hard work and steam, what can’t it do!

LikeLike

By: John Cadwallader on October 27, 2010

at 7:21 am