For a long time, it was my practice to have a pen or pencil handy to make notes in books I read. Started in high school, I suppose, but the practice really took hold in college and reached its apotheosis in graduate school. In those college days, I used a pen in textbooks, and, if I recall correctly, the favored implement was the thin, thin BIC Accountant, which I memorialized a few posts ago, HERE. That baby let one underline passages in even the most densely-set copy and still stay between the lines. I know, I know, I should have used a pencil and then erased all those marks before I returned the book to resell at Follett’s Bookstore. Let me tell you a secret, fellow students. You’re going to get a dime on a dollar for those books, if you’re lucky, no matter what. Save yourself the time and effort. (Will students be able to resell e-books?)

Fear not. For nice books, I did use pencil, when it didn’t seem appropriate to write in a nicely-printed volume with a 49-cent pen, but there’s nothing that makes the act of reading more visceral than marking up the book.

Over the years, my marginal commenting script grew tinier and tinier, and I was able to take most of the notes for Shakespeare and the Victorians almost entirely in the books themselves in a miniscule hand. That skill was really put to the test in graduate school, as I wrote frantically to capture comments of Professor Tonsor in Intellectual History as he blazed through “The Idea of Progress” and “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” (which, if you’ve ever wondered, is where the phrase, “paradigm shift” originated; it is a truly monumental book that I heartily recommend).

I did a more thorough job of note-taking in my core courses in English, since I had a firmer fundamental grasp of the subject, particularly Chaucer, which was taught by the eminent E. T. Donaldson (that’s Ethelred Talbot!). Dr. Donaldson had retired from his post at Yale and was availing himself of one of the opportunities that come to noted scholars in their emeritus years, accepting visiting professorships for a year or so with other big-league English programs with good faculties and libraries, and I was at Michigan during his term there. Think of Dimaggio or Aaron making their final tour of the major leagues in the last years of their careers. (If you still have your tried-and-true copy of the “The Norton Anthology of English Literature,” you’ll find Donaldson at the head of the list of editors.)

Dr. Donaldson’s instruction was witty, charming, entertaining and no more rigorous than he wanted it to be in any given session. It consisted primarily, in my recollection, of his relating amusing anecdotes about odd word derivations and interesting scholarly discoveries and disputes over interpretation. My marginal notes for that class still survive in my battered copy of The Canterbury Tales, preserving quite a few of his little gems.

For the most part, I pray that no one ever bothers to read any of those hundreds and hundreds of lines I wrote in those books. I am positive that they are vain, pretentious and, almost certainly, dead wrong. Take, for example, my one venture into pure philosophy at the end of senior year: Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason.” Over my head? You might say so. Still, I knew I was going to have to write something that resembled human thought in a paper at the end of the class, so I scribbled away earnestly, highlighting and commenting to the best of my ability. I guess I can still distinguish between a priori knowledge and a posteriori knowledge, but that may be about it, aside from recalling one line from Kant, “The mind is a unity which unifies.” Cool, huh? Write it down and you might remember it for 35 years.

After school, the marginal-comment practice gradually faded, and I gave up underlining and commenting on every book I read. One guy got me going again: Thomas Pynchon. One of his trademarks is to introduce a new character every page or so throughout an 800-page novel, and to maintain six or eight distinct plot lines, each with its own set of characters that sometimes do intersect and sometimes do not. After I’d been through the first couple of his books, I figured out that making a few notes here and there might help. For example, one could look back over a couple hundred pages to remind oneself of the origin of the talking sentient mechanical duck in Europe when it shows up again in America in “Mason & Dixon.”

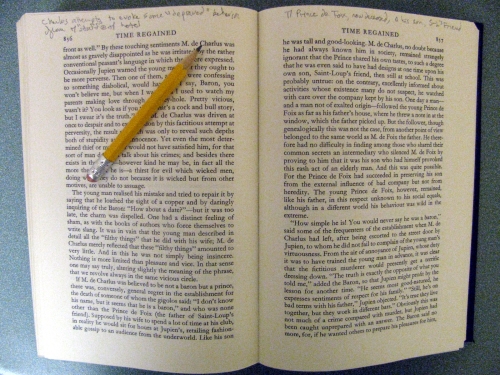

Therefore, I was ready when I launched into “Remembrance of Things Past.” I knew that M. Proust, while perhaps not Mr. Pynchon’s equal in rate of characters-per-page, was going to generate a LOT of people and events to keep track of during the next 3,500 pages or so. (Read my introduction to this exercise in reading Proust HERE.) I armed myself with a new #2 and started in, noting the first entry of new characters, underlining some of the unbelievable word wizardry he generates, putting notes at the top of pages that indicate the main action, and marking a few of the mind-boggling sentences he routinely tosses off, ones which easily cover a page of solid text.

As luck has had it, I’ve kept that same pencil over the many months I’ve progressed through the book. It’s my Proust Pencil, sharpened as needed, until now, with fewer than 300 pages to go, it’s been ground down to the stub you see here, not even long enough to stick behind my ear with any security. I’ve never gotten sentimental about which pen or pencil I used, so I hope this isn’t some new idiosyncrasy — starting a new pencil on each new book.

Now, I don’t really think I’ll read Remembrance of Things Past again in this life — at least not all of it — though I’d be willing to, believe me. But it is such an utterly remarkable book, so memorable, that I do consider that I might go back to look through some of the sections again. One idea I have is to read at least one of the seven books — probably “In the Shade of the Young Girls in Flower” — in an alternate translation, just to compare what a more contemporary translator does with the text. In that case, all those hundreds of marginalia will be there. I hope they’re not as lame as the comments I left behind in Kant!

© Brad Nixon 2009, 2017

haha, i wrote this big long thing and then deleted it.

i never made notes or underlined my college textbooks, nor do i with my reading now, though i’m not trying proust either, and it might have helped me with steig larrson’s “the girl who played with fire”. all those swedish names.

mostly i wanted to comment on the textbook biz.

as you know it’s a huge rip-off, but you might not know that it’s not the campus store that’s ripping you off, even though they’re to blame for nearly everything.

the campus store, even the dreaded chains, are in an odd spot. they don’t pick a large percentage of what they stock, and very little competition on

who to get the stock from. when i worked there,

we normally got a 20% off the retail price for new textbooks, 23% from the more generous companies, and down to nothing from the less generous.

the textbooks are picked by the professors, who are lavished with free copies and supplemental materials, and dog know what else, by the textbook companies. i remember once a sales rep for a company that no longer exists, sat at my desk, using my phone and explained to someone that “oh, the bookstore isn’t our customer, they’re just the delivery system, the profs are our customers.” thanks.

part of the text department’s task is to try to trick the professors into telling them what books to order. you’d think this would be easy enough, try it. sometimes, in a fit of whatever, the instructor will want to use an old edition, one he/she knows already, this bites the student later, as old editions don’t really sell back, but that’s the bookstore’s fault for being the face of the crime.

one of my favorite personal book adoption stories happened one fall term when a student approached my work area and told me “yeah, the professor said the bookstore didn’t order the book in time, and that’s why we don’t got one.”

“got one?” ok, i went through the bin where we kept the forms from the profs, i found his class and showed it to him. “we sent this out in may,

see that date? that’s when we asked them to have it back to us. see this date? (yesterday at the time) that’s when your instructor turned the order in, so, technically, he is correct.” that danged bookstore!

i asked a sales manager for a major textbook company, that still exists, why the prices keep going up. he glanced around and told me, “because you sell used books. it you only sold new books, we wouldn’t have to change editions so often.” ah, so it’s the bookstore’s fault again!

used books come from companies like follett’s.

at our store, some representatives from a competing used book company operated our buy-back. anything being used next session, 50%

off the current list price, not the purchase price.

if not, well, it’s kind of up to that company what they’ll give, it’s their money, they’re buying, but it’s pretty much the same, or was, industry wide, and i think squat sums it up.

though one time i sold a book back 5 years later for the same price i bought it for as a student.

the used book company then sells the books to college stores at 50% off the current list price,

30% off new books that profs have sold to the

companies. still, this is the bookstore’s fault because the service is provided there.

another heart breaker is the refund period. drop a class? no worries, bring your text back for a refund. oh, you wrote your name inside in pen, spilled coffee on it, underlined the first chapter? sorry, the refund flier we stick in every purchase?

did you read that? we sold you a new book, we have to get a new book back, or we can’t send it back. i know, i know, it’s unfair, but that’s how it is.

where the bookstore does make some decent money, and nobody seems to mind, is notebooks and sweatshirts, backpacks, shotglasses and things like that, that have a niiiiiice discount, and nobody bats an eye about buying or wants to sell back.

well, this has gone too long already, sorry!

LikeLike

By: brian on December 4, 2009

at 5:05 pm

Brian. Thanks. Great stuff. Appreciate getting the professional POV.

LikeLike

By: Brad Nixon on December 5, 2009

at 10:52 am

groan! soapboxing on one tiny side point of your blog! sorry man!

LikeLike

By: brian on December 5, 2009

at 1:30 pm

Heck no. That’s the point. And that’s the wonderful thing about blogging. Here I write all this material as if I’m the world expert, and in passing mention something I really know nothing about. Then, voila, my readers and I get expert testimony. Keep ’em coming.

LikeLike

By: Brad Nixon on December 5, 2009

at 2:20 pm

carp! how did i reply twice?

anyway, of course i quickly remembered talking with a member of the business faculty, we were discussing the pricing policy. “but the books don’t cost you that!”

to which i replied, i hope not too nastily, “no, see, we buy books at one price and then sell them for more, that’s how we make our money, you know, like retail?”

our biggest, and probably only, defenders were the store’s student employees who, apparently with some firmness sometimes, would set their fellows “straight”

about being ripped off by the bookstore.

one odd policy was that staff and faculty, the ones with an income, got a discount at the student store, but the students, of course, didn’t. when ever we had a sale, it was usually larger than the discount, but there’d always be a prof

(what is it with the school of business?) often several, who’d ask “do i get my discount on top of that?” “you can have your discount, or the sale price, but not both.”

STOP ME!!!

LikeLike

By: brian on December 5, 2009

at 3:44 pm

ok, one more adoption story then!

it was summer term, the fall book requests were at that point a month over due, and this professer i knew slightly came in and said “sorry to be so late…”

and grinning i pipe up “i know, your dog ate it. no, your sister tore it up. no, it was in the car and your dad took it to his house and forgot to get it back to you.” all the usual reasons the profs get for late papers. “no,” he said, “my house burned down”.

d’OH! winner of the sensitive bureaucrat of the month award.

which, of course, reminds me of another pointless story. one of the sociology profs was in trying to get some exception or other to a policy, which i hated to decline, but steadfastly declined to do. he said “i understand, this is classic bureaucratic behavior, at one end, they make these decisions, and never have to think of them again. at your end, you see the results of the decisions, and have to carry them out. one end has no repercussions, the other end has nothing but repercussions. it’s classic!” i still didn’t make the exception, but called the manager, who, of course made the exception and a face that indicated i should have.

LikeLike

By: brian on December 5, 2009

at 3:30 pm

ok, one more adoption story then!

it was summer term, the fall book requests were at that point a month over due, and this professer i knew slightly came in and said “sorry to be so late…”

and grinning i pipe up “i know, your dog ate it. no, your sister tore it up. no, it was in the car and your dad took it to his house and forgot to get it back to you.” all the usual reasons the profs get for late papers. “no,” he said, “my house burned down”.

d’OH! winner of the sensitive bureaucrat of the month award.

which, of course, reminds me of another pointless story. one of the sociology profs was in trying to get some exception or other to a policy, which i hated to decline, but steadfastly declined to do. he said “i understand, this is classic bureaucratic behavior, at one end, they make these decisions, and never have to think of them again. at your end, you see the results of the decisions, and have to carry them out. one end has no repercussions, the other end has nothing but repercussions. it’s classic!” i still didn’t make the exception, but called the manager, who, of course made the exception and a face that indicated i should have, which then begged the question, why have a policy anyone can over-ride?

LikeLike

By: brian on December 5, 2009

at 3:31 pm

I don’t know if you’re a fan of Billy Collins, but he has an excellent poem titled “Marginalia” about the business of making your own notes within a text. My English major roommates got to meet Mr. Collins last April during his visit to our campus (I was in musical rehearsals, naturally). Their favorite quote of his from that day is: “If you’re majoring in English, you’re majoring in death.”

My biggest foray into marginalia, besides blocking notes, was with Pynchon as well- The Crying of Lot 49. A little less ambitious than his other works, but I enjoyed it a lot.

LikeLike

By: Katie Nixon on December 5, 2009

at 7:19 pm

Excellent. Thanks for that pointer to Mr. Collins. My own reading of Mr. Pynchon also started with Lot 49, (just about 40 years ago) so you are on your way. Fabulous discoveries await you!

LikeLike

By: Brad Nixon on December 5, 2009

at 7:30 pm