One of a series celebrating the 100th anniversary of the U.S. National Park Service.

All the posts I’ve written about U.S. National Parks and Monuments to-date describe scenes of natural beauty, often wilderness, some of them also including ruins from ancient occupants, including Mesa Verde National Park and Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

There are also 89 National Historic Sites in the National Park Service system that preserve the homes of famous Americans or places where important historical events occurred: pivotal locations for understanding the history and heritage of the country. The names are familiar to most Americans: Andersonville, Fallen Timbers, Ford’s Theater, Golden Spike, Jamestown.

Manzanar National Historic Site, located at the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California, is one of those places. Notably, it is not a witness to the greatness and stunning achievements of a freedom-loving people: It is a monument to prejudice and injustice that it behooves us to remember.

In 1942, at the outset of WWII, heeding suggestions that people with ancestries linked to combatant nations represented security threats, the U.S. government ordered the internment of U.S. citizens of foreign ancestry and resident aliens, including those with German and Italian roots, but primarily 110,000 people of Japanese origin. The large majority were U.S. citizens, born in the U.S.

With only a few days notice, thousands of citizens had to determine what to do with their houses and household goods. They were not simply being relocated; they were being dispossessed. Most sold their properties at a loss.

They were shipped to “relocation centers:” 10 purpose-built facilities in remote areas of Arizona, California, Oregon and Washington. Manzanar was the first center constructed. Today, the centers are referred to by a more accurate word: concentration camps.

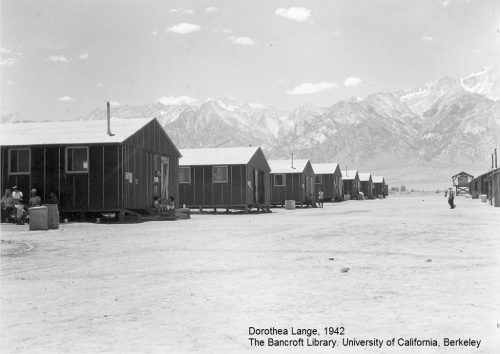

Manzanar held more than 10,046 people at its peak. Incarcerees lived in crowded, uninsulated wooden barracks.

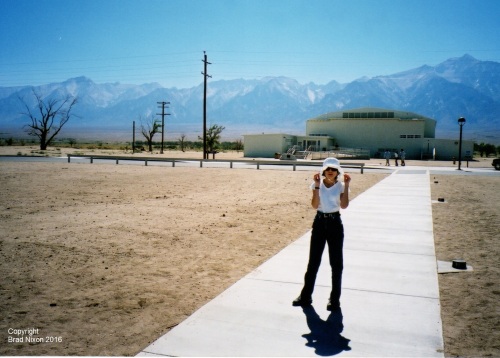

Today, few structures remain on the site, which is mostly barren, covered with chaparral. The center’s auditorium still stands, and contains exhibits that depict life at Manzanar between 1942 and its closing in 1945.

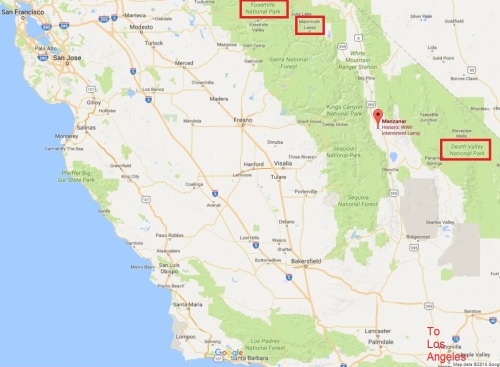

Most of the people interned in the camps were from the West Coast, 90% from the Los Angeles area. Manzanar is 230 miles north of Los Angeles.

Life at Manzanar provided little or no privacy and few creature comforts beyond basic subsistence. The desert climate at about 4,000 feet elevation was harsh: hot in the summer, cold and snowy in winter, beset at all times by almost constant wind and dust that pervaded everything. The residents had only communal facilities, including latrines.

They made the best of things. There was work, ranging from $8 per month for unskilled labor to $19 per month for professionals. They formed sports teams, choirs, made gardens, built a chicken ranch and published a newspaper, the Manzanar Free Press. An ironic title?

There was beauty there. The Sierras rise out of the high desert, and on many days there’s a view of the tallest peak in the contiguous 48 states, Mt. Whitney, 14,505 feet (not visible in photo below).

Manzanar is a word from the language of the Paiute tribe of Native Americans. It means “apple orchard.” The Paiute were expelled from the land where Manzanar stands in 1863. Many of them were forced to walk 200 miles to Fort Tejon in one of the forced relocations of Native Americans called the Trails of Tears. Lest we forget.

The Japanese Americans sent to the camps left behind farms, fishing boats and shops. They were instrumental in developing the growing agricultural economy of the West, introducing dry land irrigation. Some farmed land only a few miles from my house. They lost that land. Others fished or worked in the harbor a mile downhill from me. They were moved away.

The 30,000 residents of L.A.’s Little Tokyo lost most of their worldly possessions and the place was left a ghost town.

While their parents and families were incarcerated in Manzanar, Tule Lake and the other centers, 26,000 men of Japanese heritage served in WWII, many of them volunteers. They primarily served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which, combined with the 100th Infantry Battalion of the Hawaiian Territorial Guard, fought with distinction in North Africa, France, and Italy. With 9,846 casualties, the 100th/442nd had the highest casualty rate and was the most highly decorated Army unit for its size and length of service.

Lest we forget.

No Japanese Americans were charged with espionage during WWII.

In 1988, the United States formally apologized for its actions and offered $20,000 reparation to each of the surviving internees. 89,219 internees or their heirs received a total of $1.6 billion.

When at Manzanar, visit the exhibition in the auditorium in order to “see” the camp as it was, for there is little there today other than overgrown foundations of buildings long gone. It’s an evocative experience to stand in the desert and reflect on a horrendous error. The wind blows, the mountains tower to the west. Manzanar is a place of remembrance.

Why We Must Remember

A new executive administration will take the reins of U.S. government in January 2017. It is closely aligned with and supported by sympathizers calling to restrict the freedoms of Americans and residents who match “profiles” defined by bigotry and racism. In blatant violation of the equal rights and protection for all citizens guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution, some suggest that the internments of 1942 offer a desirable precedent to once again restrict the freedom of people and imprison them based on race, religion or national origin.

That idea is incompatible with the Constitution, and ignores the harsh lesson of Manzanar and the other U.S. concentration camps.

It can happen here. It has happened here.

Lest we forget, Manzanar stands silent, empty, forlorn. Our witness. Our reminder.

Practicalities

Manzanar is located on U.S. Route 395, which is also the road to reach Death Valley, Mammoth Lakes/Devil’s Postpile and the Tioga Pass entry to upper Yosemite Valley (red squares). About 3-1/2 to 4 hours from Los Angeles (below bottom of map), 7 hours from San Francisco (on left of map).

The site is open daily from dawn to dusk. There are no fees. The former auditorium is the Visitor Center, parking is free. The center includes extensive exhibits and artifacts about life at Manzanar. The park provides a driving tour guide, the best way to survey the extensive site. The cemetery contains remains, and while photography is permitted, it merits appropriate decorum. Be careful turning off or onto busy Route 395. Vehicles are approaching at high speed across level ground, and will be upon you quickly.

For other Under Western Skies articles about U. S. National Parks, please click on the entry under “Travel” in the Categories listing in the right-hand column.

© Brad Nixon 2016, 2018. Barracks row photograph by Dorothea Lange, 1942; The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley. The text of this article draws heavily on material from the National Park Service Manzanar website.

Thanks for the timely and thoughtful post.

However, actually, I would differ a little with you and say that the new administration is “closely aligned with and supported by sympathizers calling to restrict the freedoms of Americans and residents who DO [delete “not”] match ‘profiles’ defined by bigotry and racism.” It seems to be more clearly defining itself that way with nearly each new appointment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: La Boheme on November 20, 2016

at 4:49 pm

I blame whoever invented English. It’s a confusing language. Good catch. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Brad Nixon on November 20, 2016

at 9:03 pm

The British invented the English language. Americans can’t be held responsible for the confusion the language causes. 😂

I have heard that French 🇫🇷 is a far more precise language. 👍 However, I don’t speak enough of it to be able to verify this claim. 😺

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: La Boheme on November 20, 2016

at 9:17 pm

If I were going for precision, I’d switch to German. My French and German readers are welcome to join this discussion. All language is freighted with uncertainty.

LikeLike

By: Brad Nixon on November 20, 2016

at 9:38 pm

On further reflection, Mathematical or computer language is probably the most precise we have. 🤓 However, my skills in these areas are very limited. Therefore, I do not speak with authority. 😳 This is the case with most of my opinions. 😸

LikeLike

By: La Boheme on November 20, 2016

at 10:04 pm

[…] via Manzanar National Historic Site – Lest We Forget — Under Western Skies […]

LikeLike

By: Manzanar National Historic Site – Lest We Forget – Under Western Skies – Nomad Advocate on February 16, 2017

at 8:16 am

Thank you for the link. A site and a time worth recalling.

LikeLike

By: Brad Nixon on February 16, 2017

at 8:41 am